auto_rate: Performance in detecting linear regions

Source:vignettes/archive/auto_rate_performance.Rmd

auto_rate_performance.RmdNote

This page has been archived and will not be updated. This is

because it was submitted as part of the publication of

respR in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, and has been

retained unchanged for reference. Any results and code outputs shown are

from respR v1.1 code. Subsequent updates to

respR should produce the same or very similar results.

Introduction

The function auto_rate uses rolling regression and

kernel density estimation techniques to automatically detect the

most linear regions in respirometry data. The dimensionless

nature of the function, however, also allows it to be applied to any

serial data.

To our knowledge, the methods we use here are novel, and not reported

in past publications involving linear data detection and analysis of

biological data. Olito et

al. (2016) describes a different, though robust, method to detect

and rank linear segments in data using their R package,

LoLinR. A comparison of auto_rate and

LoLinR’s methods are shown here.

The performance tests that we present here are limited but

comprehensive, and provide a starting point in generating the data

necessary for users to make informed decisions on using and further

testing auto_rate for their own purposes. Users

should be aware that noisy, strongly fluctuating data could

cause unpredictable, unwanted results to be returned. For example, while

we have had generally good results with our own data, intermittent flow

respirometry data where O2 is fluctuating up and down between periods of

use by the specimens and flushing the respirometry chamber are likely to

confuse the algorithms. Users should always examine the outputs of

auto_rate (and indeed other functions in

respR) to understand where returned results occur within

the data and that they are representative of the question of interest.

We have made this as easy as possible, and designed the package

specifically to not be a ‘black box’ and at every stage make the user

aware of what is going on through plotting results and their locations

in the context of the entire datasets, and in the console outputs.

Testing the linear detection method of auto_rate

To ensure that auto_rate performs as intended, we

created two internal functions designed to test the accuracy of our KDE

techniques to detect linear data. The first function,

sim_data(), generates a random dataset which contains both

linear and non-linear segments. The second function,

test_lin(), specifically performs auto_rate

repeatedly on randomly generated data and aggregates the performance

metrics obtained to assess and visualise the accuracy of the KDE

technique. Both functions are published with the respR

package, thus anyone can use them – as we show below – or run them with

their own input paramters.

Generating simulated data for tests

sim_data() is used to randomly generate three kinds of

data based on the type argument, which we briefly describe

below. It accepts inputs to customise the length of the data (no. of

samples), the type of data (described below), the degree of noise as

specified by the standard deviation of the data (default 0.05), and a

preview toggle to plot and visualise the simulated dataset.

“Default” data

sim_data(type = "default")

A non-linear segment is first generated using a sine or cosine

function with a random length of

floor(abs(rnorm(1, .25*len, .05*len))), where

len is the total number of observations in the data defined

in the function argument, and a random amplitude of

rnorm(1, .8, .05). This data segment is appended to a

linear segment with a randomly-generated slope computed using

rnorm(1, 0, 0.02). The shape of the dataset is designed to

mimic common respirometry data whereby the initial sections of the data

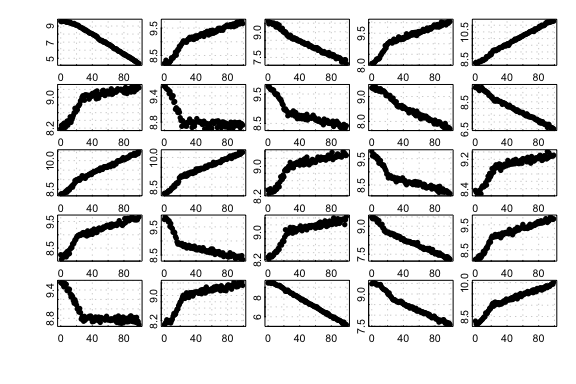

are often non-linear. Here we show 25 randomly-generated plots created

by the type:

25 randomly generated default-type simulated datasets

“Corrupted” data

sim_data(type = "corrupted")

Same as "default", but “corrupted” data is inserted

randomly at any point in the linear segment. The data corruption is

depicted by a sudden dip in the reading, which recovers. This event

mimics equipment interference that does not necessarily invalidate the

dataset if the corrupted section is omitted from analysis. The dip is

generated by a cosine function of fixed amplitude of 1, and the length

is randomly generated using

floor(rnorm(1, .25 * len_x, .02 * len_x)), where

len_x is the length of the linear segment.

Thus, to detect the valid linear segment, auto_rate will

need to omit the initial non-linear segment, ignore the dip, and then

pick the longer of the 2 remaining linear segments that are separated by

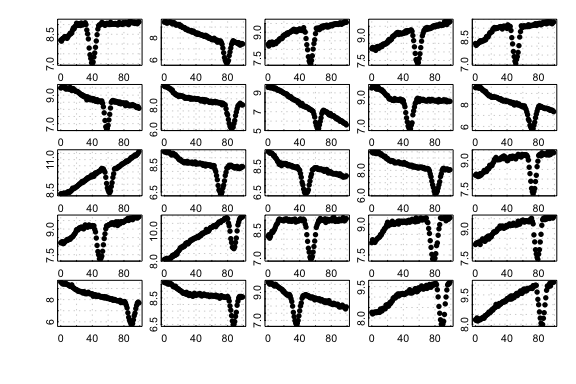

the dip. Here we show 25 randomly-generated plots created by the

type:

25 randomly generated corrupted-type simulated datasets

“Segmented” data

sim_data(type = "segmented")

Same as "default", but the data is modified to contain

two linear segments. The slope of the second linear segment is randomly

chosen at approximately

0.5

to

0.6

of the first linear segment (i.e the slope is always a magnitude smaller

than the first linear segment).

Thus, to detect the correct linear segment, auto_rate

would need to correctly omit the initial non-linear segment, and also,

ignore the end segment of the data as it has a different slope. Here we

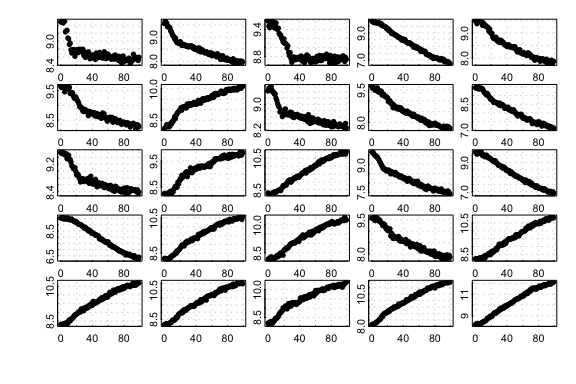

show 25 randomly-generated plots created by the type:

25 randomly generated segmented-type simulated datasets

Test conditions

To quantify the performance and accuracy of auto_rate’s

linear detection technique, the function test_lin() runs

the linear detection technique (method = "linear")

iteratively and extracts specific output parameter for analysis. The

parameters include:

- The length of the true segment ();

- The length of the detected segment that is correctly sampled (). Here, we also call such data “true”;

- The length of the detected segment that is incorrectly sampled (). Here, we also call such data “other”;

- The slope of the true segment (, or true rate); and

- The slope of the detected segment (, or detected rate).

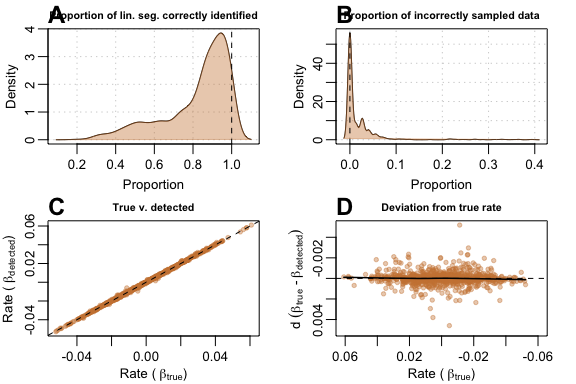

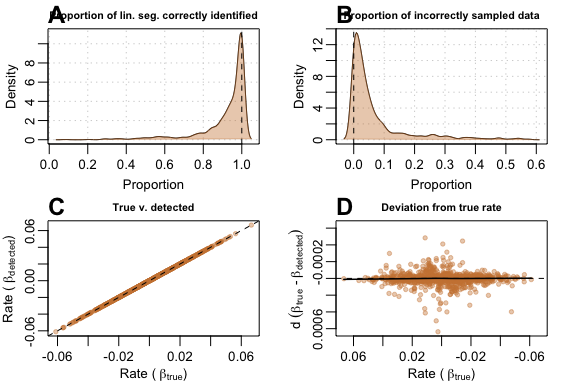

From the above data, we can generate four kinds of performance metrics for visualisation:

- A density plot of the proportion of the linear segment correctly identified. Each data point is a measure of .

- A density plot of the proportion of incorrectly-sampled data. Each data point is a measure of .

- A linear regression plot, where each data point is a measure of of (y) as a function of (x);

- An x-y plot of the deviation between and . Each data point is a measure of .

We performed test_lin() with 1,000 iterations, for all

of the three kinds of data produced by sim_data()

("default", "corrupted", and "segmented"). To

check performance on different data lengths, we repeated the tests using

100, 200 and 500 data points. The output of our performance test is

avaliable from within the package as a data object called

test_lin_data.

# NOTE: Functions take some time to run

# Test on data of length 100 samples -------------------------------------------

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "default"-type data

set.seed(123)

default100 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 100, type = "default")

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "corrupted"-type data

set.seed(456)

corrupted100 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 100, type = "corrupted")

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "segmented"-type data

set.seed(789)

segmented100 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 100, type = "segmented")

# Test on data of length 200 samples -------------------------------------------

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "default"-type data

set.seed(123)

default200 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 200, type = "default")

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "corrupted"-type data

set.seed(456)

corrupted200 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 200, type = "corrupted")

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "segmented"-type data

set.seed(789)

segmented200 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 200, type = "segmented")

# Test on data of length 500 samples -------------------------------------------

# This performs 1,000 iterations of auto_rate on a "default"-type data

set.seed(123)

default500 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 500, type = "default")

# This performs 100 iterations of auto_rate on a "corrupted"-type data

set.seed(456)

corrupted500 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 500, type = "corrupted")

# This performs 100 iterations of auto_rate on a "segmented"-type data

set.seed(789)

segmented500 <- test_lin(reps = 1000, len = 500, type = "segmented")How do I know if the tests are actually running and detecting segments?

test_lin() can perform tests in a very cool and visual

way – at the cost of speed. The argument plot, when set to

TRUE, can show us exactly the detected segments at every iteration. Try

it!

# Try this code below. WARNING: Will run and plot visuals 20 times.

x <- test_lin(reps = 20, len = 500, type = "segmented", plot = TRUE)Results

“Default” data

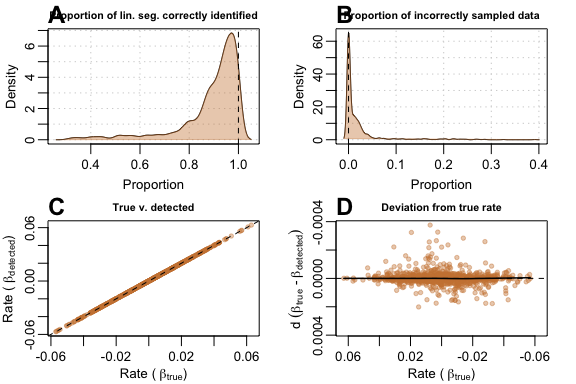

Results were very encouraging; when run on data with 100 samples,

(A) auto_rate correctly detected a large

proportion of the true segment in general, and (B)

incorrectly sampled only a small amount of other data.

(C) Comparison of

against

showed very stable detection across all slopes, even when slope values

approached zero. This was evident in (D) where roughly,

the maximum

values had

deviation from the

values across all values of

,

even for values close to zero:

plot(test_lin_data$default100)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on default-type data with 100 samples

Tests on larger sample data sizes of 200 and 500 revealed that

auto_rate performed better when provided with bigger data.

When used on data with 500 samples, auto_rate generally

(A) detected a larger proportion of the true data and

(B) was less prone to sampling incorrect portions of

the data. (C) Linear regression had a

of 0.999, and (D) deviation was

10

smaller than when sample size was at 100:

plot(test_lin_data$default500)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on default-type data with 500 samples

“Corrupted” data

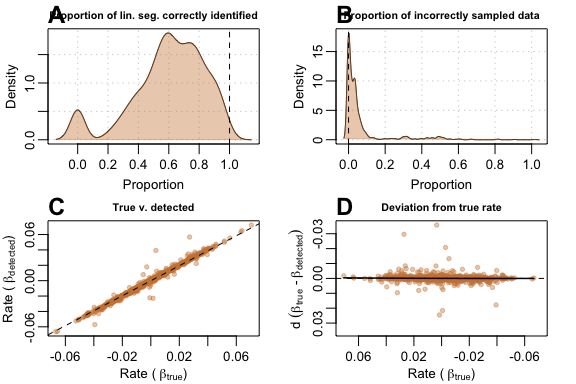

In this challenging data scenario auto_rate had a

tendency to under-sample the linear segment. As this particular type of

data consisted of two linear segments separated by a “dip”, the function

also sometimes (A) detected the shorter segment as the

top-ranked result, resulting in the correct estimate of

,

but the wrong linear segment detected. Thus, the function may

incorrectly sample none of the linear segment (B), but

only rarely; in most cases, it still identified the right segment, and

incorrectly sampled only a small amount of data. (C)

Comparison of

against

showed stable, but relatively noisy detection of the true rate across

all slopes when compared to its performance with “default”-type data.

(D) The deviation plot showed that performance was

genrally poorer at values close to zero.

plot(test_lin_data$corrupted100)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on corrupted-type data with 100 samples

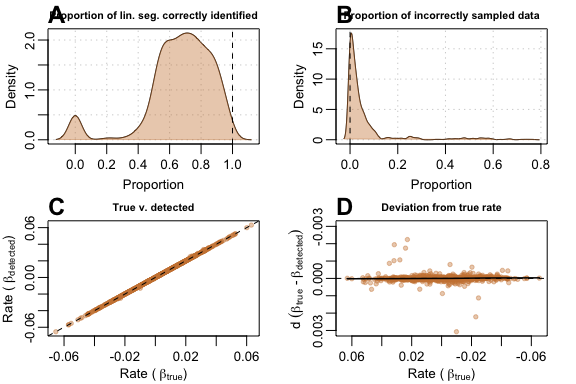

Again, auto_rate performed better when provided with

bigger data. At 500 samples the same issue where the shorter linear

segment was incorrectly selected still persisted (A),

but (B) the function sampled incorrect segments less

often, (C) linear regression of

against

had a better goodness of fit and (D) deviation values

from

were substantially smaller with seemingly fewer poor estimates when

slope values approach zero.

plot(test_lin_data$corrupted500)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on corrupted-type data with 500 samples

“Segmented” data

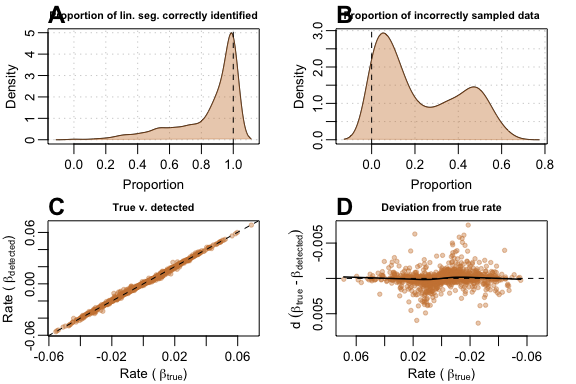

This type of data is the most difficult to handle as

auto_rate needed to disregard the curved, but

increasingly-linear top portion of the data, and also discard the slight

degree of change in slope towards the end of the data. Thus,

auto_rate performed well in many cases, but poorly in

others. In the majority of cases, (A) when it managed

to sample the linear segment, it did so for a very large fraction of the

data. (B) It performed less well at avoiding incorrect

sampling, since it sometimes selected the other linear segment. However,

(C) the plot of

against

showed that it still performed surprisingly well most of the time,

despite the errors, and (D) the deviance from the true

rate appeared to be poorer when slope values are closer to zero.

plot(test_lin_data$segmented100)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on segmented-type data with 100 samples

Again, with a larger dataset, auto_rate’s performance

was substantially better. With a 500-sample dataset, many of the issues

that occured in the previous test were better resolved. The function

(A) correctly sampled the right segment most of the

time, and rarely sampled other data or the other linear segment

(B). (C) Linear regression of

against

had a

of 0.999, and (D) deviations from

were much smaller in magnitude.

plot(test_lin_data$segmented500)

Performance metrics for auto_rate on segmented-type data with 500 samples

We did not report any of the results for 200-sample size datasets,

but users are free to call the data object test_lin_data

and plot the results, or run their own analyses using the functions we

provide.

Summary

In this limited testing on relatively small datasets, we have shown

that on datasets of around 100 records in length auto_rate

performs quite well, although with some occurrences of data

mis-characterisation. However, when datasets are around 500 in length

its performance is radically improved. This pattern holds across our

three test data types characteristic of respirometry data:

"default" (non-linear to linear data segments),

"corrupted" (data with an obvious erroneous drop-out), and

"segmented" (non-linear to multiple linear segments). The

use of auto_rate on datasets larger than this is likely to

be even more accurate in identifying valid linear regions of data.

Despite the overall good performance, this does serve to illustrate

that users should always inspect and explore their data, and the results

of analyses for obvious errors and that the results are characteristic

and valid answers to the question they are asking of the data. We have

this made this as straightforward as possible in respR

through always outputting by default plots with results highlighted in

the context of the entire datasets, and useful summary output in the

console. There is also extensive support for exploring data and results

via the base R plot(), print() and

summary() functions.

References

Olito, C., White, C. R., Marshall, D. J., & Barneche, D. R. (2017). Estimating monotonic rates from biological data using local linear regression. The Journal of Experimental Biology, jeb.148775-jeb.148775. http://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.148775